At the 50th anniversary celebration of the origins of the international trade system in 1998 in Geneva, Nelson Mandela in his speech said: “The developing countries must accept that we want to be fully part of the WTO, and that includes improving the management of the world trading system to ensure that our economies do develop.”

This was an important message. The World Trade Organization (WTO) had evolved from the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) – on African soil, in 1994 in Marrakesh. Mandela’s view remains important in the context of the now-30-year old WTO’s 13th biennial Ministerial Conference, in Abu Dhabi, UAE, from 26-29 February.

Currently, 44 African countries are members of the WTO, with nine further countries holding “observer status”; only two are not affiliated with the WTO at all. African countries currently account for 27% of full members. Notably, the vast majority of these countries joined the WTO before China, which became a member in 2001.

Despite this, not much has changed for Africa within the world trading system over the past 30 years. If anything, it has worsened. In 2023, the African continent accounted for 2.7% of world exports. Back in 1973, that share was 4.8%. Meanwhile, the continent’s share of world imports is higher than exports today at 2.9%, but in 1973 it was lower at 3.9%.

Over the decades since world trade rules were introduced, the continent has fallen into a persistent trade deficit with the rest of the world. A significant reason for this is the character of the rules. The WTO is much like its predecessor, the GATT. That was designed and agreed by 23 countries in 1947, none of which were African – at the time most African countries were still colonies.

Admirable goals, on paper

On paper, the ambitions of GATT and now the WTO are admirable: to expand market access by reducing explicit and implicit trade barriers; to provide a platform for settling trade disputes; and to provide technical assistance and capacity-building to support market access.

In practice, the rules are designed in a way that constrains the ability of Africans to improve the world trade system in the way Mandela hoped.

For instance, the WTO does not vote. It pursues negotiation through one country, one voice: but negotiation powers are incredibly imbalanced. Many African countries – responsibly – limit their delegations, due to low budgets.

Typical WTO practices such as holding “informal” and “green room” meetings leave out smaller economies. Negotiated agreements on issues important to African development – such as the degree of permitted agricultural subsidies in wealthy countries – can, and often do, go against African interests, or at best de-prioritise them.

Another example is the dispute system. This is expected to be a major and contentious issue at the Abu Dhabi ministerial.

In the 27 years of the WTO dispute settlement system’s history, African countries have acted as respondents or complainants in only 13 cases – just over 2% of all cases. Fewer still have been resolved. There is no doubt that most African countries would launch more complaints, especially with respect to protectionist measures imposed by high-income economies, if they had the power, support and financial resources to do so.

A further example is found in the intellectual property (IP) rules promoted by the WTO. These are predicated on the theory that innovation requires strong IP protection, for example through long-term patents and copyrights – often attributed to a 1962 paper by American economist Kenneth Arrow. The WTO uniformly promotes these rules to all countries, with a few concessions in terms of the substance and timing of obligations for developing and less-developed countries.

But this theory has been questioned. Instead, open innovation – where various groups participate in product development and innovation – has been proposed.

Moreover, the WTO promotes some policies ostensibly to protect people from food hazards – known as sanitary and phytosanitary measures– or to protect health – such as compulsory licensing of medicines. It has been well documented – especially during the Covid-19 pandemic experience – that these policies hinder many countries’ access to essential products.

Prospects for the Abu Dhabi meeting

The question is then: might this 13th WTO Ministerial Conference make any difference? Can it help Africa double or even triple its share of world trade, as the WTO’s Director General – former Nigerian finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala – has said should happen? She has talked, for example, about encouraging a new approach to global trade – “re-globalisation”, – for instance to diversify supply chains, including those in Africa.

Indeed, both agricultural subsidies and reform to the dispute settlement system are expected to be the major items on the negotiating tables at Abu Dhabi.

But even when the WTO has proclaimed a major success, as it did in 2015 in Nairobi, promising to “benefit in particular the organisation’s poorest members”, the reality is a little murkier.

In the past, the WTO secretariat and lead negotiators have sought to protect its reputation by focusing on the least contentious areas. The EU and the US had already reduced to close to zero a narrow range of agricultural subsidies that were finally banned in the Nairobi text. That made it easy for them to sign up. Meanwhile they continue to use other types of agricultural subsidy, safe in the knowledge that putting these on the agenda will be deemed “too tough”.

The AfCFTA is not a refuge

Now that African countries have the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), in effect since 2021, readers may think that Africa shouldn’t worry about the WTO or about re-shaping trade with others. Can Africa not rely on its own trade, and just let the WTO continue?

I would humbly suggest that this is a naïve approach. Today, Africa has have two options alongside promoting the AfCFTA. it either exits the WTO because it is not working for Africa – or, as Mandela encouraged, pushes hard and creatively to reshape the world trading system in its interest.

The latter might work, starting in Abu Dhabi. The revival of the WTO’s dispute resolution mechanism is being discussed there, after being stifled by the US since 2016. In the negotiation rooms African negotiators could collectively extract a shift in the composition of this so-far unhelpful body, in exchange for bringing it back to life.

In the negotiation rooms where export bans on food and fertiliser are proposed as the key problems to be solved in agricultural markets, African negotiators could work to take this off the table.

They could replace these with proposals to ban “carbon border taxes”. It has been estimated that the EU’s border tax could cost the African continent $25bn per year from 2026 – an amount similar to what all OECD countries spent on humanitarian aid in 2022.

It is clear that the WTO needs a major makeover in its 30th year. Growing African internal trade will not solve the distorted market forces that have led to Africa’s increasing trade deficit with the world. If the WTO and its advocates want African support, they need to start demonstrating that it can work for Africa. And as Africans, we need to demand and propose ways that it can do that.

This article was originally published on Africa Business. To read it, click here.

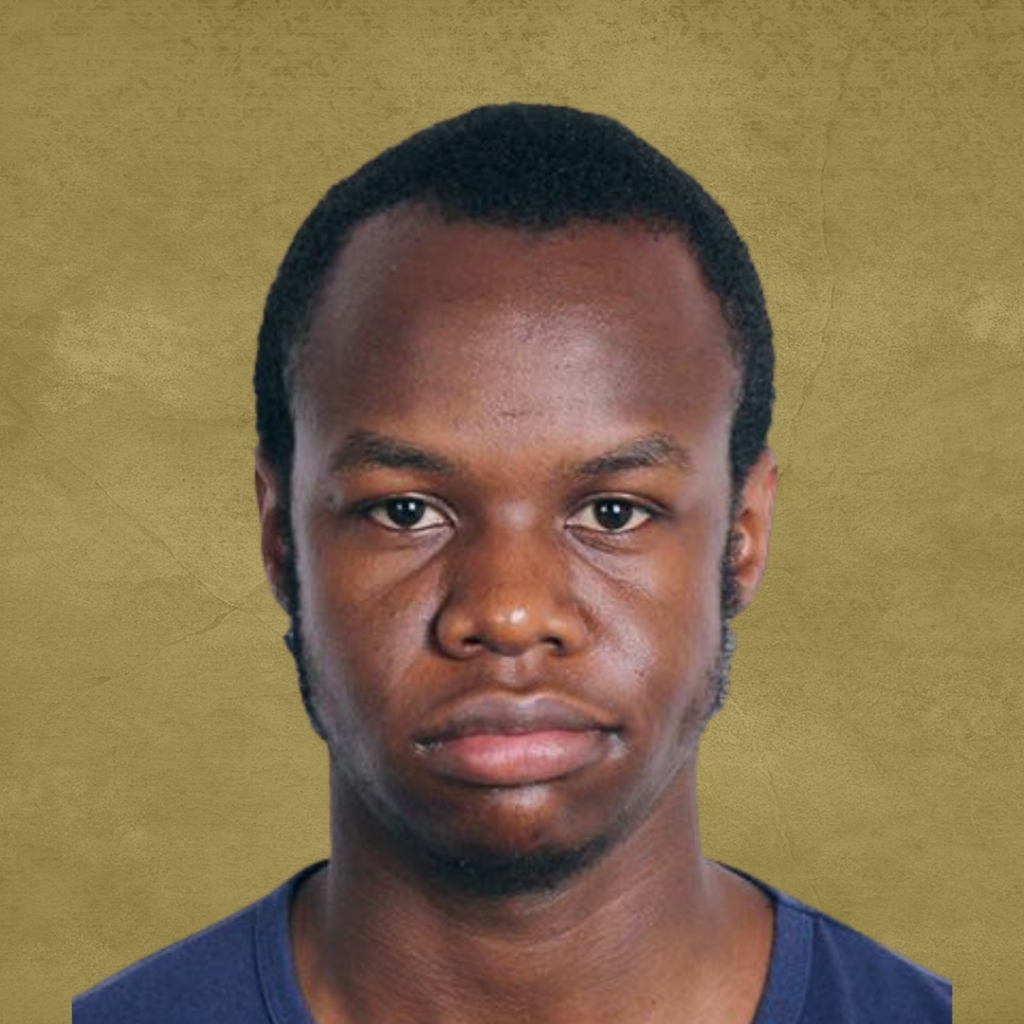

Hannah Ryder. Hannah is CEO of Development Reimagined, an independent African-led international development consultancy based in Beijing.